TREATISE:

. Quantum

Nodal Theory

ROMALDKIRK:

. Village

. Reservoirs

ESSAYS: COSMOLOGY

. Infinity

. Universe

. Dark Matter

ESSAYS: PHILOSOPHY

. Free Will

. Representation

. Conditionals

. Postscript

ESSAYS: ORGAN MUSIC

. Practising

. British Organs

. Hymn Playing

. Music Lovers

QUIZ QUESTIONS

. Quiz Archive

SERVICES

. Book Reviews

Practising the Organ

Hector C. Parr

The study of the pipe organ (and its electronic imitation), its composers and repertoire, and the art of playing it, can occupy a lifetime. A few pages on the web can make only a small contribution, but there are several things I want to say which others may like to read. This essay looks at the art of practising; I am hoping some younger organ students may find useful the thoughts of an older organist as he looks back from the other end of his career.

INTRODUCTION

What qualifications have I to tell other organists how they should do their practising? Perhaps my justification is rather negative. For the greater part of my life I have practised badly, and thereby restricted considerably my competence as an organist.

True, I passed my examinations and became a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists more than forty years ago, but I sometimes wonder whether I deserved the honour at that time. Perhaps I was fortunate in having examiners who recognised musical understanding and commitment, and rated them more highly than accuracy and precision, qualities whose development had been handicapped by poor practising technique. I had by that time "learnt" most of the major Bach works, and much of Mendelssohn, Franck and Vierne besides; my performances satisfied me at the time, but I now realise their shortcomings. The habits of a lifetime are hard to break, and I now must admit that some of these works are beyond redemption, and will never be played well.

Now in retirement, with more time to spare for both playing and thinking, I have learnt much about the art of practice, and it is ironic that my fresh approach enables new music to be learnt more rapidly than formerly. Life was indeed busy during my working years, and I blamed the shortcomings in my musical performances on shortage of time. But my present approach to practising would not only have improved their standard, it would also have saved time. Today it is a great joy to find that those few major works of Bach and others which I had never previously tackled can now be learned far more quickly, and played to a higher standard, than if I had attempted them earlier. If this essay can prevent any younger organists from making my mistakes, I shall indeed be pleased.

HABIT

When one watches a highly skilled artist at work, be he a musician, a painter, a sculptor or a sportsman, one is tempted to say, "That is impossible!" Many of the highest accomplishments of mankind demand years of practice, and are made feasible only by our remarkable facility at forming habits. Much of an artist's skill is habitual and achieved without thought, and only thus is the seemingly impossible accomplished.

But the mechanism of habit formation is blind, and is two-edged (if I may mix metaphors). Good habits and bad are formed with equal facility. It follows that, while learning any art, we must make as much effort to avoid the formation of bad habits as in cultivating the good.

This is what has taken me most of a lifetime to learn. Much of the organ repertoire is so wonderful, and the wish to play it so overwhelming, that as a youngster I got great satisfaction from every new piece I tackled, pretending to be giving a performance. I was quite a good sight-reader, and could skim through a page at full speed, getting roughly the right effect, despite many wrong or missing notes. Without thinking, I assumed that if I did this often enough, it would eventually come out right; in fact the habit-forming instinct did work, and I became fluent at playing that page, complete with all its wrong and missing notes! If you are at the start of your musical career, please don't make the same mistake!

EQUIPMENT

To avoid such pitfalls there is a simple secret: practise systematically. For a start, collect together your tools, as any good craftsman would do. So what are our tools of trade?

A pencil and rubber, of course. Every organ should always have these immediately to hand. I also include a pad of "Post-it" notes, those useful adhesive labels that can be stuck on your music, and then removed again without tearing a hole. (One organ I knew always had an additional item, an ashtray. Fortunately most organists do not find this essential.)

But I have two other items which are always ready, a metronome and a tape recorder. The paragraphs that follow will make it clear why these are indeed essentials.

WHY PRACTISE?

No, this is not a silly question, and deserves some attention. There are, I suggest, four reasons why we cannot sit down with a new piece of music and give a good performance without practice.

(i) Most of us are not sufficiently good sight readers to take in all the notes quickly enough to play them at sight at the required tempo.

(ii) The unique difficulty of organ playing lies in the degree of independence required between hands and feet. Often we can play without difficulty the right hand, or the left hand, or the pedal part, but putting all three together may demand much practice.

(iii) If the separate parts themselves cause difficulty, the reason is likely to be that our fingers and feet lack the technique needed to execute them faultlessly without study and practice.

(iv) Even if all the above problems did not exist, we could still not expect to give an artistic interpretation of a new piece of music, with all the subtle detail that entails, without thought, experiment and practice.

Of these difficulties, the first and second are the easiest to deal with. The chief argument of this essay is the importance of slow practice, and when tackling a new piece I have a simple rule of thumb to determine how big a problem it will pose. When the chief difficulty lies in reading the notes, (i), or in the degree of independence required, (ii), then if I can play it reasonably well at sight at half speed, I know systematic practice will soon bring it up to standard. Usually an intensive hour's work (preferably spread over a number of practice sessions) will more than suffice to perfect one page of music. If, on the other hand, the difficulty is technical, (iii), if the hands and feet are required to perform gymnastics of a sort not encountered before, the same process of systematic slow practice is again the best way to master the difficulties, but it is less easy to predict how much practice will be needed.

If in the past your practising has been haphazard, you will be greatly surprised how the technique I describe below can speed up the learning of new music, and will make music accessible which in the past you have considered well beyond your capabilities. If your limit in the past was the "Eight Short", you should now be able to tackle the "A major"or the "G major". If it was the "D minor", you should now try the "Great G minor". If you could just cope with a Rheinberger Sonata, why not try the Reubke or the Eroica?

You will notice that I am not asserting that systematic playing is all you need to solve problems in the fourth of the above categories. Practice cannot make you a musical player, sensitive to the many qualities which distinguish a great performance from a competent one. But if the technical difficulties of a work are conquered efficiently and without anxiety, there is then more space for the interpretive faculties to develop, as they certainly will if you truly love the music you play.

A FEW "DON'T"s

For five years I lived in a boarding school, where my study was separated by only a thin wall from a piano practice room, euphemistically known as "The Salon". So I can claim unrivalled experience of the many wrong ways to practice.

The first of these I have already described, for it was my own failing in earlier years. As explained, playing music beyond one's immediate capacity at speeds which leave behind the debris from frequent accidents, is no way to learn a work, and is fatal to the development of technique. It undermines the ability ever to give accurate performances.

An alternative and equally unsuccessful method is to correct every wrong note after it has occurred, ignoring the destruction of the rhythm which this entails:

I have had pupils who would turn up week after week and play the same wrong note, followed immediately by its correction, so that I knew in advance when this was going to happen. Their habit-forming mechanism had assumed that both notes were part of the piece. None of these pupils made it to the concert platform or the cathedral organ loft.

Others would play a passage wrongly nine times, growing increasingly frustrated, and breath a sigh of relief when the tenth attempt was successful, before going on to the next passage. Now what is the habit-forming mechanism to make of this? The wrong version has had nine times as much practice as the correct one. But this mechanism cannot read music; how was it expected to know which of the repetitions were right?

The habit-former, however, is not quite as sensitive as the previous paragraph may suggest, for if it were, how would a cricketer ever learn to hit the stumps? In his early bowling practice he must surely miss more often than he hits. The secret lies in the pleasure he gets when he is successful, and his displeasure when he fails, of which the habit-former is aware. At one time I always used to say a polite "Sorry!" if anyone was present when I played a wrong note. Then one day I was page-turning for one of our finest organists as he made a recording, and he greeted a wrong note (which is actually quite undetectable on the recording) with a loud "Damn!" I have done the same ever since, even when no-one is present, and I am certain my playing has benefited as a result. It sends a clear message to the habit-former to delete the last bit of data before it gets stored in the memory. And in any case, a musician never apologises for his playing; if he is doing his best there is nothing for which to apologise.

Another bad practising technique is to play the notes and ignore the rhythm completely. Each note or chord is carefully read, and is played as soon as it has been worked out. At least the long-suffering habit-former is given only right notes to remember, but how is it to know that there is such a thing as rhythm?

My final castigation is more controversial, but I do insist upon it. Except when conquering very unusual difficulties I never practise the hands or the pedal part separately. Instead I find a speed, however slow, at which I can play all three parts correctly, and in correct time. "But if I detect some sort of error", you may protest, "how do I know in which part the fault lies?" I have a simple solution which is always successful. Suppose you suspect the left hand is doing something wrong. Try playing all three parts, but with the right hand and the feet on keyboards with no stops drawn, so that only the left hand is allowed to sound. Any mistakes or irregularity there will then be cruelly exposed.

PREPARATION

Enough of the negative. Now how do we start work on a new piece? If you have one or more recordings of the work, although in general I do not recommend studying these in detail at this early stage in your practising, I do make an exception here, and listen to these recordings once only. You do not want your ultimate performance to be a copy of someone else's interpretation, but it is valuable to have some idea of the goal to which you are working.

If, on the other hand, you have no recordings, then you may break another of my rules, and play through the whole work once at full speed (making certain no-one can hear you). In either case, the object is a simple practical one, to determine what seems to you to be the speed at which this work should be played. Check carefully against the metronome and write it down. In the course of the slow practice which the piece is to undergo you are likely to lose track completely of the correct speed. Not only have you now got a record of this, but as your practising proceeds you will have a measure against which to check progress.

You will also have a broad picture in your mind of the interpretive task which lies ahead. What sort of registration will be demanded? Is the work mainly polyphonic, chordal or lyrical? Will it require many stop changes? What about swell pedalling? Will you play it in strict tempo, or is flexibility called for?

The next tasks can all be undertaken at your desk rather than at the console. You should begin by drafting out a provisional registration scheme, and pencil it lightly on your copy, or use Post-it notes. This can all be changed later, but it is important to know which manuals you will be using, since fingering and other decisions will depend upon it.

If the piece incorporates any ornamentation, now is the time to work out in detail how it will be performed. If there is a mordent, does it start on the principal or the auxiliary note? If there is a trill, how many repetitions will it entail? It is essential that, in your slow practice, the ornaments are slowed down in proportion, so that the correct number of repetitions are made. Only in this way can good performance habits be formed.

Still seated at your desk, and before attempting any playing, you should work right through the movement, thinking out carefully the broad details of your phrasing and articulation, and marking them in your copy. Although some of the detail may change as practice proceeds, it is necessary to have a draft pattern at this stage. Not only will this ensure consistency throughout the work, but it is needed before you can decide questions of fingering and footing. A passage which poses difficulty if played legato is often easier to finger when you know the positions of phrase endings and breathing points. And pedal passages which look forbidding because of an absence of rests often become simple if a detached style is appropriate.

And now is the time to tackle these problems of fingering and footing. Do not mark your copy more than necessary, but enough should be written to ensure that the same fingers and feet will be used every time you play the work, and also that passages which appear twice or more are played the same way on each occasion. Otherwise your habit-former will become confused.

If the work is difficult to read, this also is the time to look at the harmonic basis of the most demanding bars. What at first may appear to be a random collection of accidentals often has a simple underlying harmonic structure, and bearing this in mind as you practise can make it unnecessary to look at most of the notes. Vierne's Toccata from Book 2 of the Piéces de Fantaisie provides a good illustration. The penultimate page looks particularly frightening (p.40 of the Lemione edition); the key signature has five flats, but almost every one of the semi-quavers is preceded by an accidental, usually a sharp or a natural. The harmonic analysis, however, is quite simple. The manual parts of the first three bars contain only minor common chords, in B flat, E, E flat, A, A flat and D minors respectively; if you mark these lightly on your copy you will need to read only one or two notes of each chord as you practise, and will not need to look at any of the accidentals. The next four bars contain only major common chords, which you should mark similarly. The whole of the following eight bars are built from chords of the diminished seventh; if you are familiar with these chords (and there are only three), you just need to mark on your copy the places where the chord changes. Then much of the final page is built up from one or other of the whole-tone scales (there are only two), and augmented triads (of which there are four). In fact, if you are sufficiently advanced as a player, this fine Toccata is an excellent test-bed on which to try out the recommendations of the present article; practised systematically, with consistent fingering, it lies beautifully under the fingers.

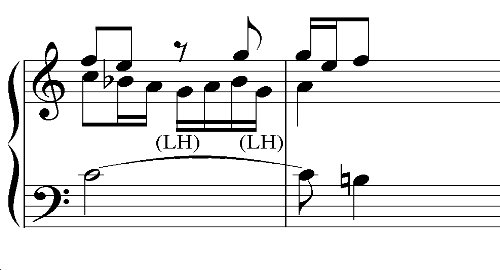

It is surprising how often a difficult passage can be simplified by playing one or more notes in the left hand part with the right hand, or vice versa. This illustration (from Bach's well-known "Giant" Fugue) provides a simple example.

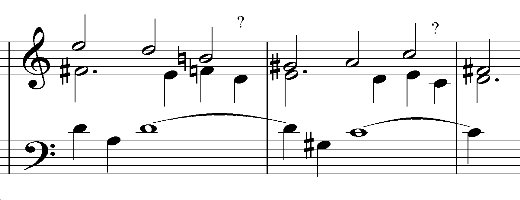

And in contrapuntal music there are frequently awkward moments where two parts run into the same note, and we must decide whether to repeat the note and so spoil one part, or leave it unrepeated and so spoil the other (as in the next illustration, from Bach's Canzona). This is the time to resolve all such questions, and mark your solution on the score to ensure consistency in your practice.

In some types of music, use of the swell pedal needs consideration. Look carefully at the moments when you are likely to make a crescendo or a diminuendo; your toeing and heeling may have to be modified to release a foot from other duties. Mark it all in your copy.

If, at a later stage, you are embarrassed by the thought that others seeing your music may suppose all these pencil marks to indicate an inferior memory, you can always erase some of them as the habits form.

THE SYSTEM

We are now ready to start the real practice. If wrong notes or faulty rhythm are not to become ingrained, this practice must be at such a speed that they do not occur. Apart from its tempo, our playing should be perfect. At first this might entail extremely slow tempi, and it might seem that such practising will be boring; but provided we are playing good music it is always possible to derive enjoyment from it at any speed. We know it is not what the composer intended, and we can look forward to the day we get it up to speed. But by temporarily suspending our critical faculty we can nonetheless enjoy it as a different piece of music from its ultimate realisation. We must resist the temptation to push the tempo beyond the limit where accuracy and timing are sacrificed. And we must attend meticulously to details of fingering and footing, to articulation and the performance of ornaments. At this stage it is not necessary to play loudly, but in order to form the right habits we should always use the correct manuals.

People differ in the length of the section they tackle at one time, some working on a complete movement, and others doing just one phrase. And some enjoy playing little games as they practise. Make yourself play a passage three times without any error, not even a "split" note. Much more demanding is to play it three times in succession without error; your punishment for a mistake is to start again at number one. When a passage persistently refuses to play itself accurately, do not despair; all it means is that you are playing too fast for that stage of your practising; reset the metronome and try again.

But one's approach must depend also upon the range of difficulty within a movement. Much time is wasted in playing a piece from beginning to end if the chief difficulties lie only in isolated sections. Then the best approach is to begin each day's practice with the most difficult section, and try to increase its safe speed. It is pleasing to find, on the following day, that this no longer seems the most difficult part, and some other section assumes that role. In pieces which are of more uniform difficulty, a good plan is to choose a suitable speed and work right through from the beginning. When a passage proves risky at that tempo, spend several minutes on that section at reduced speed before proceeding.

Whatever method is adopted, speeds should be checked from time to time against the metronome. In the case of a complex movement with several changes of tempo, it is worthwhile drawing up a chart to show after each day's practice the speed at which each section can be played without error. In this way the player can see at once the previous few days' progress, which section is most in need of practice, and how far away the goal remains. Then next day, begin each section just a little slower than the highest speed achieved previously. Proceeding this way, it is gratifying and often surprising to find oneself playing difficult sections safely with a fluency which seemed impossible a few days ago. The goal is reached when the safe tempo is just a few per cent greater than that decided upon originally.

THE FINISHING TOUCHES

Technical proficiency, of course, is only a part of musical playing. The artistry that compels an audience to listen, and brings them into close contact with the composer's deepest thoughts, transcends anything that can be explained in terms of moving fingers and feet. But provided the player has a clear idea of the ultimate effect it is hoped to produce, and a picture of the work's architecture as a whole, the interpretation should develop without conscious effort as one practises. A good teacher can analyse many of the elements that make up an artistic performance. He or she may say, "Shape that phrase with a slight slackening of tempo, and detach the last note", or, "Point to that climax by dwelling slightly on that top note", and the pupil will attend to these details because he is told to. But to the musical performer, they form in his consciousness before he can put them into words.

It is now time to finalise the registration, and the logistics of its management. Controlling the swell pedal, pushing pistons, and even turning pages, all require patient practice if they are not to upset the final performance. I remember watching one of our country's great organists spend twenty minutes practising adding Great to Pedal as he prepared for a recital. Needless to say, the action was performed perfectly at the performance.

And then is the time to make one's first recording of the complete work. It has often been said, very truly, that the commonest mistake of instrumental performers is a failure to listen to their own playing; it is so easy to hear instead the sounds you hope to make rather than those you are actually producing. I remember once playing most of Bach Chorale Prelude, using a Stopped Flute and Nazard for the solo line, before realising that the Flute was not sounding; the resulting solo line was a twelfth above the pitch written, but my inner ear had provided the 8 foot tone that the organ failed to produce.

Some of the faults which are most frequently overlooked in this way are rhythmical. Almost all of us are prone to allow random variations of tempo, and in particular to hurry passages which are more difficult than their surroundings. And because, in a sense, the mind is working faster in these places to cope with the extra complexity, there is no way by which we can be aware of our varying speed while playing.

So make a recording, and listen to it. If this makes you exclaim, "My playing is not as bad as that!", this just proves how deficient is your listening. But the tape recorder is a very cruel teacher. Any sensitive human teacher makes a note of your mistakes, and then decides which ones to mention, and which to leave for another lesson. The recorder tells you all of them at once. If you find this too much to bear, one little tip is to keep your recording until tomorrow before playing it back. Somehow we can hear our faults in a better perspective after a lapse of time, and are more ready to hear also the virtues which our playing displays.

Sometimes I sit down with pencil and paper while listening to such a recording, and pretend I am writing an adjudicator's report on someone else. The notes one writes can be a great help in putting real polish into one's performance, and quite often there is no need to make much conscious effort to remedy the faults they pinpoint. Merely being aware of them may be sufficient; it is particularly gratifying that rhythmic unsteadiness of the type described above often resolves itself this way.

If the attempt is not perfect, record it again, and again. If you plan to keep the final version as a record of your best ever performance of the particular work, this should provide sufficient incentive to persevere. And your criticisms can become ever more searching. Is the tonal variety just what you wanted? Is the balance between parts exactly right? Do your touch, articulation and phrasing bring out the part writing clearly? Are your tempi correct? Above all, does the whole performance integrate into a single artistic whole?

THE RECITAL

Special problems present themselves if you are to perform on an organ with which you are unfamiliar. Many recitalists like to do at least six hours' practice for a one-hour performance, and yet still find no time to waste if they are to be ready for the recital.

Firstly, try out briefly every stop individually, followed by all the standard choruses, such as Great diapasons at 8', 8'4', 8'4'2', and 8'4'2'Mixture. Then try the quiet combinations on the Swell, the reeds and the Full Swell. If the organ uses tracker action, find out whether coupling keyboards together leads to heavy touch. Test the feel of the Swell Pedal, and the range of crescendo it produces. Proceeding in this way you will quickly learn the character of the instrument. It should then be possible to choose suitable registrations with very little trial and error. If the piston combinations are fixed, learn what each one gives you; if they are adjustable, be ready to set them for the most critical of the works you are playing.

Then you can play through your whole programme in the correct order, carefully writing all your registration instructions on your copy, or on Post-it notes. If the organ has the advantage of a Sequencer, you will need to stop playing at each registration change, set it up correctly, and make a note of the number on your copy.

Remember it is not only the organ you are getting to know, but the building also. Are some of your tempi a little fast for the acoustics, or a little slow? If the building is resonant, do you need a more detached style here and there to preserve clarity? If the acoustic is dry, should you play a little more legato?

Then, finally, play straight through your programme again, stopping only if a piston combination needs changing, or something further must be written down.

And so to the actual performance. You have so much to think about that any pre-recital nerves will soon evaporate. Your mind will be in top gear, and so there is a danger of playing just a fraction quicker than you intend; this is easily compensated for by playing everything just a trace slower. A good audience will make no sound while you play, and you may be unable to see them, and yet somehow you will know if they are listening intently and enjoying the music.

If all goes well, the combined effect of wonderful music, a fine organ in a sympathetic building, and the response of an appreciative audience, should give you great satisfaction. If you are aware of imperfections in your playing, remember that what may seem to you the difference between a good and a bad performance, to a listener is likely to be scarcely noticeable. You are comparing your performance with the best you have ever given in practice, but your audience can make no such comparison. The standard of your playing depends very little on how you feel on the day; far more important is the quality of the preparation you have made during the months of practice beforehand.